site author: Anthony Wheeler email: anthonywheeler72@hotmail.com

Definition of Art

In order to engage in a meaningful discussion, reasonable efforts must be made to distinguish one thing from another (an art object, say, from an artichoke). The notion of ‘Art’ is notoriously hard to define, and it’s unlikely a consensus regarding its precise meaning will ever be realized.

Adorno goes so far as to assert that “The concept of art is located in a historically changing constellation of elements; it refuses definition.” (1) Mikel Difrenne appears to agree, when he writes:

But then…how can we determine which is the work of art, worthy of becoming an aesthetic object for us?...The work of art is whatever is recognized and held up as such for our approval…By accepting the judgments and preferences of our culture, we waste no time in trying to discover what the work of art is, and how it evokes aesthetic experience, without deliberating endlessly over the choice of these works. We need only place all the odds of a venerable tradition on our side. Unanimously accepted works of art will be our most reliable guides to the aesthetic object and to aesthetic experience. (2)

Except that unanimity doesn’t exist, and never will when it comes to judging art objects, so this approach remains limited. According to an anonymous dissertation, the author asserts that “Analytical aestheticians seem to have made it their job to deny the possibility of such a definition [of art] and they may be right.” (3) He (or she) goes on to paraphrase Weitz’s conclusion that “no true definition of ‘art’ is possible, and that the best we can do is procure an enumeration of existing works.” (4) He (or she) quotes George Dickie’s definition:

A work of art in the classificatory sense is (1) an artifact (2) upon which some person or persons acting on behalf of a certain social institution (the Artworld) have conferred the status of candidate for appreciation. (5)

According to the author, “[this definition] hardly alleges more than the simple answer to the question ‘Why should this thing be an art work?’ ‘…because people say so.’ As a definition, enabling people to create or recognize new works of art, however, it is highly inconsequential. Participants in the art world who confer art status to new non-art objects must be ready to provide aesthetic reasons for such conferral.” (6) But apparently these ‘participants’ feel little urgency to provide such aesthetic justification for what they consider art objects. Finally, the author concludes with the following definition:

It is my thesis that ‘art’ can be defined recursively: something is a work of art if it conforms to acknowledged artistic procedures…and these procedures are or should be acknowledged as artistic once certain of their typical instantiations occasion some specifiable experience. (7)

This definition provides little help. Art is something that ‘conforms to acknowledged artistic procedures.’ Acknowledged by whom? What are ‘artistic procedures’? This definition seems as circular, self-referential and subjective as the ones the author begins by disputing. None of them mark a clear boundary, nor provide insight as to what makes art different from everything else. Taking a positive step forward, Dufrenne asks:

Rather than falling back on opinion at the outset, why not try to discover a criterion intrinsic to authentic works? (8)

This is exactly what we will attempt, as boundaries need to be provisionally drawn in order to determine what the defined realm contains, and when borders have been transgressed. Casually accepting toothless definitions such as ‘art is anything an artist says it is’ emasculates any meaningful discussion about art before it can even begin. Adorno makes the point when he writes “It is virtually tautological to claim that the determination whether an artwork is an artwork depends on the judgment whether it is…” (9) Terry Eagleton insists that “any term which tried to cover everything would end up meaning nothing in particular, since signs work by virtue of their difference.” (10) As David Daiches confirms, something that “might mean anything” means exactly “nothing.” (11) And art always means something.

Every working artist—including those who write novels—should develop a clear idea of what they are doing, and why. They should spend serious time and intellectual energy deciding for themselves what distinguishes an art object from everything else, and what it takes to actually create something that might qualify. It is not necessary to agree with any particular definition, including the one presented below; but a prospective artist must develop a clear understanding for him or herself. Perhaps the following discussion will provide the necessary stimulation.

James L. Weaver makes the following effort:

As an artist and Art History instructor, I would have gladly, five years ago, passed on the following definition- ART: “Based on esthetics, the act of original creation, by manipulating a medium of public objects or events that serve as deliberately organized sets of conditions, having a definite beginning and end, for an experience in a qualitative mode.” (12)

As a definition, this seems a bit vague (what does “experience in a qualitative mode” mean?) but at least he makes a good go at providing a meaningful distinction. He then proceeds to indicate the difficulty of defining art in today’s world:

However, I now predict that within five years, all major university-level “required” texts whose titles fall in the category of “The History of Art”, will, and certainly should be, titled: “The History of Esthetic Experiences” as none of today’s art scholars or writers appear, understandably, capable of defining what presently passes for...art. (13)

Prior to presenting our best effort, we will take a non-exhaustive survey of what others think. The dictionary defines art as:

Human effort to imitate, supplement, alter, or counteract the work of nature. The conscious production or arrangement of sounds, colors, forms, movements, or other elements in a manner that affects the sense of beauty, specifically the production of the beautiful in a graphic or plastic medium.

There are several weaknesses with this definition, particularly as it situates art relative to ‘nature’ and ‘beauty,’ neither concept of which is fundamental to art. Ayn Rand provides one of the more deliberate and thoughtful definitions, when she defines art as a

Selective re-creation of reality according to an artist’s metaphysical value-judgments. (14)

While all art, without exception, involves some form of deliberate ‘selection’, reality is never ‘re-created’. Fundamentally for humans, all reality is created by the individual out of biological life-blood and reflections of the actual universe. The form of a specific creation may span the width and breadth of the human universe, and includes many objects that are neither meaningful, nor particularly artistic. For this reason, her definition seems far too broad and vague to helpfully distinguish one category of objects (or acts) from another. Ronald Merrill derives his definition of art from Rand’s:

A man-made object or process the function of which is to induce a sense of life in the observer. (15)

‘Sense of life’ is a central concept for Rand, which she defines as:

a pre-conceptual equivalent of metaphysics, an emotional, subconsciously integrated appraisal of man and of existence. (16)

Given that everybody sports some kind of ‘sense of life,’ and owns some combination of ‘metaphysical value-judgments’, any particular creative act will certainly be influenced by these personal factors, but it seems unhelpful to include this in a definition designed to identify that which sets art apart from everything else, given the likely ubiquity of these human attributes.

In addition, Merrill’s definition appears to make art ‘induce’ something everyone already has. Perhaps what he meant is that a work of art expresses the creator’s sense of life in a manner that is perceived—consciously or subconsciously—by the observer. But even if this is the case, the indefiniteness provides wide latitude for transgression and misunderstanding.

What follows is a quick survey of quotes and quips relating various definitions of art (attribution provided where possible):

Art is anything that people add to their ‘output’ which is not functionally necessary and is other than the default properties of that output.

Art is not the imitation of nature but the imitation of natural beauty. (17)

A form of human activity created primarily as an aesthetic expression, especially, but not limited to drawing, painting and sculpture.

What is art? That whereby forms are transmuted into style. (18)

What is a day and what is life? A block of marble that God gives to you to make a work of art. (19)

[Art is] the creation of beautiful or significant things.

If the language of nature is mute, art seeks to make this muteness eloquent. (20)

Objects created by humans that have aesthetic value or express symbolic meaning, including drawings, paintings, and sculpture.

Nature itself is a totality, and the movement into the inscrutable depths of total vitality is fate. The movement upward from these inscrutable depths is art. (21)

Human endeavor thought to be aesthetic and have meaning beyond simple description. Includes music, dance, sculpture, painting, drawing, stitchery, weaving, poetry, writing, woodworking, etc. A medium of expression where the individual and culture come together.

Art is energy shaped by intelligence. (22)

Objects or ideas created by humans which tell/show what we are thinking or feeling. Art may or may not be beautiful. Art may or may not look like something we know (recognize). Art includes painting, sculpture, architecture, music, performance, dance, and acting (drama).

An artwork is, as Beckett wrote, a desecration of silence. (23)

Human expression in sensuous form, often “for its own sake”. The word “expression” is very important, in that it implies that the motivation comes from within the artist rather than somewhere else.

Art is the indispensable medium for the communication of a moral ideal. (24)

Art is the stylization of the essential or significant aspects of a subject/concept. Art requires a theme (or at least a problem to be dealt with in action films) – a unifying idea – to integrate the material elements into a single entity.

[Art is] any human creation which contains an idea other than its utilitarian purpose. (25)

Two things have to be part of the poet and the artist: that he lifts himself above reality and that he remains within the sensuous realm. Where these two are joined, there is aesthetic art. (26)

Gadamer paraphrases Kant’s definition of art as “beautiful representation of a thought.” (27)

People would rather regard art as decoration than as a negation of real life. (28)

The history of the arts is tantamount to the discovery and formulation of a repertory of objects on which to lavish attention. (29)

Art is the blurred, scratched magnifying glass of life, specially tuned to pick out the details of the emotions and hopes of the people of the time. Rather than showing a perfect image of reality, art shows what people dream for, what they protest, their wants and needs. (30)

By art I mean three things: useful art, concerned with survival; fine art, concerned with beauty; and fashion art, concerned with conformity to social rules. (31)

Two things significantly distinguish human beings from the other animals; an interest in the past and the possibility of language. Brought together they make a third: Art. (32)

Life is conservative and flourishes only through repetition, through cliché, through formula. Just the contrary of Art. (33)

Art happens when lotsa middle-aged wimmen in long gowns and horned helmets sing real high-pitched, while dozens of guys in tuxedos saw on their fiddles, and one guy taps real light on a kettle drum. Art has pictures of plump nekkid ladies floating in the clouds, swathed in lotsa silk, with little cherubs holding the corners. Art has lotsa neat French words mixed in every now and then, words like “poulet chevalier”.

While there exists more or less merit in each of the preceding examples, the following is offered as definitive:

Art is the creation of something significantly meaningful that is essentially unique and practically useless that, without its deliberate creation, would otherwise not exist.

These are carefully chosen words, and can be further elaborated as follows:

Art is the creation – it can’t be ‘found’ or simply ‘picked up’, but instead, must be brought into existence through a deliberate creative act:

How can one deny Malraux’s view that the work is in the first place a creation? The other world which it bears in itself is not nothingness. It is the negation of the everyday world, a negation which it is necessary to credit very positively to man himself and to the origins of the human. (34)

of something – a physical artifact, event, or work

significantly meaningful – because meaning matters:

What we fear…is not death; nor even physical anguish, mental decay, disintegration. We fear most the loss of meaning. To lose meaning is to lose one’s humanity, and this is more terrifying than death; for death itself, in a coherent cultural context, always has meaning. (35)

that is essentially unique – unique in it’s most essential properties

No authentic artwork is typical. (36)

and – not ‘or’

practically useless – you can’t shovel coal with it, drive it, brush your teeth with it, or piss in it:

The value of a profane thing lies in what it usefully does, the value of a sacred thing lies in what it is. (37)

that would otherwise not exist – in other words, it could never be ‘discovered’ or ‘invented’ by someone else, ever.

This multi-dimensional view of art, then, is prominently bordered by entertainment, invention, nihilism, utility, decoration, engineering, and most extensively, the prosaic. This last perhaps most significant, as a genuine work of art offers something new and unique, neither contingent nor accidental, an object, artifact or event that presents something never before seen, heard, felt, or understood.

As in many complex concepts, no fine geometric line separates art from any of the surrounding realms, but instead, each shades more or less gradually into the other:

Both entertainment and art are meant to evoke emotion, but art goes deeper and further into the human soul than entertainment. Art conveys joy where entertainment makes you laugh. Art has tragedy, where entertainment makes you sad. Art has passion; entertainment has sex. Art goes boom where entertainment goes pop. (38)

Or to make another imprecise distinction:

Entertainment is for the masses and art is for the snobs. (39)

Vermeer's Girl with a Pearl Earring

Beauty

Beauty suffuses the realm of art, yet leaves much of it untouched, as many art objects are plain ugly. Beauty, in fact, extends well beyond the realm of art and into the world of nature, and can be found in various forms virtually everywhere: the person we love, the evening sunset, our new-born child, a mist-shrouded waterfall, a scissor-tailed flycatcher—all beautiful, yet none of them, by our definition, art (although the stylistic rendering of any of these subjects may well be):

The definition of aesthetics as the theory of the beautiful is so unfruitful because the formal character of the concept of beauty is inadequate to the full content of the aesthetic. If aesthetics were nothing but a systematic catalogue of whatever is called beautiful, it would give no idea of the life that transpires in the concept of beauty. (40)

Critics often shackle art with the need to be beautiful, and dismiss art objects as art because they are not. “The question,” Adorno writes,

of what is and what is not an artwork cannot in any way be separated from the faculty of judging, that is, from the question of quality, of good and bad. The idea of a bad artwork has something nonsensical about it: If it miscarries, if it fails to achieve its immanent constitution, it fails its own concept and sinks beneath the apriori of art….As long as the boundary that art sets up against reality has not been washed away, tolerance for bad works—borrowed from reality—is a violation of art. (41)

If we accept Adorno’s position, then we would never agree on a common definition of art, as we would be left with individual critical distinctions as to what is ‘good’ or ‘bad’ in order to establish definitional boundaries.

While one can take the legitimate critical stance and consider ‘beauty’ a necessary component of ‘good’ or ‘successful’ art, and the rendering of ugliness as ‘bad’ or ‘failed’ art, doing so remains within the critical realm, and it must be explicitly acknowledged that bad or tasteless objects might still be accepted as art if they meet the necessary parameters. “[T]he great difference between Picasso and Dali (at least according to the latter) was that Picasso’s labors were devoted to ugliness and Dali’s to beauty.” (42) While I tend to agree with Dali, and find most of Picasso’s art unworthy of serious consideration, that doesn’t make it any less artistic. The Guernica is hideously ugly, perfectly matching its thematic purpose, and as a result, ranks as one of the century’s great artistic masterpieces.

Picasso's Guernica

I consider Picasso’s rendering of the women in Les Demoiselles D’Avignon almost a desecration of feminine beauty, yet fully acknowledge the essential uniqueness and significance of the work. With this painting, Picasso shattered the traditional aesthetic norms that existed prior to 1907, liberating all artists and generating a true turning point in aesthetics.

As Sartre says, “There is no ‘gloomy literature’, since, however dark may be the colors in which one paints the world, one paints it only so that free men may feel their freedom as they face it.” (43) Nietzsche makes a critical statement, not a definitional one, when he writes:

What does a pessimistic art signify? Is it not a conradictio?—Yes.—Schopenhauer is wrong when he says that certain works of art serve pessimism. Tragedy does not teach ‘resignation’—To represent terrible and questionable things is in itself an instinct for power and magnificence in an artist: he does not fear them—There is no such thing as pessimistic art—Art affirms. Job affirms.—But Zola? But the Goncourts?—The things they display are ugly: but that they display them comes from their pleasure in the ugly—It’s no good! [note the critical judgment] If you think otherwise, you’re deceiving yourselves.—How liberating is Dostoevsky! (44)

Creation

The first major attribute of art, one that sets it apart from so many other things, is the fact that it is deliberately created. According to the dictionary, to create is “to cause to come into being, as something unique that would not naturally evolve or that is not made by ordinary processes.” Further, something is created when it “evolve[s] from one's own thought or imagination, as a work of art or an invention.”

Art doesn’t copy anything, represent anything directly, or stand in for some other element of reality. Genuine artistic achievement always results in the creation of something new. “The more one studies art,” Alfred Kazin wrote, “the more one recognizes that it is not an imitation of life, that it never comes close to actual human experience, but is an independent creation, an addition to nature rather than a description of it.” (45)

Meaning in Art

Even if an aesthetic object is not to be confused with a merely signifying object, it is nonetheless not a meaningless object. It is fully meaningful—indeed, it is saturated with meaning. (46)

Genuine art means something, contains some significant substance that impacts those touched by it. “[Henry James] can’t conceive an artist,” Leavis writes, “who is not concerned for significance. ‘Significance’…is a term that doesn’t admit of close definition…It points to the wholeness of a created work, to that which makes it one—to the principle of life that determines its growth and organization.” (47) Eagleton points out that while “Significance’s vary throughout history…meanings remain constant; authors put in meanings, whereas readers assign significance’s.” (48) “For [Musil],” Peter Watson writes, “the fundamental question was whether the soul could ever be replaced by logic. The search for objectivity and the search for meaning are irreconcilable.” (49) That would make the search itself, in Eagleton’s terms, meaningful for Musil, and significant for the rest of us.

“The writing of novels is basically a process of assigning value to human experience in the social world,” John Aldridge writes. He goes on to say

The novel, so long as we require of it a narrative form and function, must always have to do with the actions of men within the framework of a particular society; and it must also, so long as we require of it the validity of serious art, endow those actions with meaning. (50)

And where does meaning principally reside? Art Berman relates the general consensus that “meaning for humans does not exist apart from language, that language is not simply—as it is for the classic empiricists—a tool or medium through which preexistent ideas in the mind, produced by perception and a subsequent process of association that unites primary ideas into more complex ones, are shared with others.” (51)

The work is truly meaningful in its unique way only if the artist is authentic: it says something only if he has something to say, if he truly wants to say something. (52)

Even music, the most enigmatic of all art forms, contains meaning:

Music is meaningful in the extreme. For many of us it comes closer than any other human happening to communicating the possible proximity of the transcendent. (53)

Meaningless art is an oxymoron, and simply doesn’t exist.

The Essentially Unique

To be considered a genuine work of art, a particular object must be essentially unique, different from anything else that exists. Adorno writes:

The concept of an artwork implies that of its success. Failed artworks are not art: Relative success is alien to art; the average is already the bad. The average is incompatible with the medium of particularization. Middling artworks, the healthy soil of minor masters so appreciated by historians of a similar stamp, presuppose an ideal similar to what Lukacs had the audacity to defend as a “normal artwork.” However, being the negation of the spurious universal of the norm, art tolerates neither normal works nor middling ones that correspond to a norm or establish their meaning in terms of their distance to it. (54)

While an average work may be empirically unique, its similarity to others may render it common, ‘normal’, or middling in its essential features, pushing it outside the realm of art. This happens in genre fiction, and explicitly in the formula writing that characterizes modern romance. Every novel is technically unique from every other, as one text will invariably vary from the next. But not necessarily in its essentials. How ‘artistic’ or ‘literary’ a particular work can be considered will depend on essential differences between itself and every other novel. The more common the form, content, style, and execution of a particular novel, the more likely that it will remain deep within the realm of entertainment. Such novels are quickly forgotten, whereas well conceived and competently executed works that are unique will likely be read and reread, and retained within the realm of art and literature.

Notwithstanding Benjamin’s issue with mechanical reproduction and the loss of aura as an original work gets mass produced (post cards, printing presses), such reproduction does not diminish the essential uniqueness of a literary novel. Huckleberry Finn remains art, regardless of how many times it has physically been reproduced. The essential uniqueness lies in the text itself, and not in any particular physical form.

Again, grey colors the boundaries: what might in one age be considered a common object made in conformance to a pre-determined formula may at a future time be considered a work of art, particularly if few examples survive to the present. Pottery may serve as a common example, as well as early forms of personal sculpture, cave paintings, or carvings. The present tends to be over-impressed with the past, and the more distant the past the more impressed those in the present are likely to be.

On the other hand

What once was art may cease to be art. The availability of traditional art for its own depravation has retroactive power. Innumerable paintings and sculptures have been transformed in their own essence to mere decoration as a result of their own offspring. (55)

Utterly Useless

A story, like a painting, or like a symphony, is one of the most wonderful, one of the most useless, things in the world. The magnificence of a work of art lies precisely in the fact that nobody made the artist make it, he just did, and—except when one’s in school—nobody makes the receiver read it, or look at it, or listen to it: He just does. (56)

“All art is quite useless,” Oscar Wilde famously asserts in the preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray. Had he written ‘practically’ useless, perhaps there would have been more understanding and less controversy, as the lack of utilitarian purpose marks one of the principle distinctions between art and all other manmade objects:

[A]rtworks, in accord with Kant’s magnificently paradoxical formula, are “purposeless,”…they are separated from empirical reality and serve no aim that is useful for self-preservation and life…(57)

“All contemplation of objects except the aesthetic is essentially practical, and so directed toward personal ends,” Harold Bloom writes. “The poet’s genius frees contemplation from the drive of the will, and consequently the poet is able to see with a quiet eye. To see into the life of things is to see things for themselves and not their potential use.” (58) Gautier elaborates: “Nothing is truly beautiful except that which serves no purpose. Anything useful is ugly, for it is the expression of some need, and human needs are ignoble and disgusting, like his pitiful and feeble nature.—The most useful place in a house is the latrine.” (59) Nietzsche agrees: “Anything truly productive is offensive.” (60)

Humans spend the majority of their time and energy fulfilling instinctual needs: they eat, sleep, reproduce, protect themselves and maintain social relationships. Aside from individual activities in bed, the bathroom, at mealtimes, productive work dominates most days. And for the majority, the products of a particular workday typically provide other humans the ability to eat, sleep, remain safe, reproduce and maintain social relationships (farming, grocery stores, home building, fire/police, telecommunications, transportation, etc.) In total, humans spend a fraction of their time and energy on artistic activities, and yet these activities alone separate them from every other living thing. And it is for this reason that art necessarily represents that which is practically unnecessary to maintain a human life, and instead, contributes its own special pleasures:

The concept of artistic enjoyment was a bad compromise between the social and the socially critical essence of the artwork. If art is useless for the business of self-preservation…it should at least demonstrate a sort of use-value modeled on sensual pleasure. (61)

Architecture, sometimes referred to as the queen of the arts, seems to straddle the frontier between art and utility. Yet in the vast majority of cases, every element within a particular structure is strictly utilitarian, or at best, mere decoration. The most artistic of structures, those that actually mean something, such as temples (the Parthenon), tombs (the Taj Mahal), and monuments (Washington’s, for example) serve no practical purpose whatsoever.

Bridges might be considered an exception, as in many cases, that which directly supports the roadbed—be it steel strands or chiseled rock—is deliberately artistic in its design and execution, while simultaneously engineered to timelessly perform its intended function. Even so, a bridge typically doesn’t mean anything, contains no significance beyond its utilitarian purpose, and can rarely be considered essentially unique, rendering it something other than art.

With respect to the imperatives of need, the aesthetic object seems absolutely gratuitous. The painting adds nothing to the solidity of the wall, the armchair may be comfortable without being beautiful, the poem teaches me nothing about what calls for my enterprise in the world. Thus, art has been considered in some epochs as a superfluity reserved for an idle class, a luxury refused to those whom work confines in the world of tools. Through art, seeing, hearing, and reading become disinterested modes of behavior which seem dedicated to the greater glory of perception and lack any outcome of consequence. The aesthetic object promises nothing…(62)

As in most things, a proper balance must be maintained between the necessary productive work that keeps us healthy and reasonably comfortable, and artistic activities that exalt our existence:

One man cultivates the beautiful and another what is useful, but only the combination of both constitutes the true man. Usefulness cultivates itself, for it is cultivated by the general mass of people [out of brut necessity if for no other reason], and no one can do without it; but beauty must be expressly cultivated, for few people embody it and many need it. (63)

Art Does Not Have to Exist

While the creation and the enjoyment of art may be fundamental to humankind, a particular art object could easily not exist. “The objects of scientific speculation and investigation,” George Steiner writes, “however uncertain their reality-status outside the relevant hypothesis and observation, are, nevertheless, given. They are prior and determinant in ways which differ fundamentally from the ‘coming-into-thereness’ of the aesthetic. The choices made in the sciences, the forward motion of the collective scientific enterprise, are phenomenologically imposed as those in the sonata or novel are not...Only in the aesthetic is there the absolute freedom ‘not to have come into being’. Paradoxically, it is that possibility of absence which gives autonomous force to the presence of the work.”

Furthermore:

The experiencing of created form is a meeting between freedoms. The famous question at the roots of metaphysics is: ‘why should there not be nothing?’. This very same question underlies any grasp of poetics and of art. The poem, the sonata, the painting, could very well not be. Except in the trivial, contingent perspective of the commission, of material need, of psychic coercion, the aesthetic phenomenon, the shaping act, is at all times and in all places at liberty not to come into being...In the immense majority of adult men and women, early impulses towards the making of art have withered away altogether. The production of executive forms by the sculptor, composer or poet is a supremely free act. It is liberality in essence and, rigorously considered, a wholly unpredictable choice not not to be. (64)

The artistic act, even when creating realistic forms, results in objects that would otherwise not exist, objects that nobody would perceive or experience without its deliberate creation. And not just inner realms. The action involved in walking down a dark alley at night seen from overhead is likely—unless we live over such an alley—never to have been personally experienced by ourselves, yet the sensations and images associated with such a scene may be reasonably encountered in film, painting, or literature. Annie Dillard writes:

William Gass says,… “The aim of the artist ought to be to bring into the world objects which do not already exist there, and objects which are especially worthy of love.” Always crucial to these thoughts is the caveat that art is lovable and has beauty neither according to its novelty as a newborn object on earth nor according to the lovableness and beauty of the worldly objects it represents, but only according to its internal merits as art. (65)

Annie indicates important border markers between art and everything else. Something new may be meaningless, excluding it from the artistic realm; an ugly object may prove essentially unique and meaningful, granting it entry.

Test case: Modern Art

Given that modern art has systematically attacked definitional boundaries, and explicitly attempted to subvert the very notion of art itself, applying the proposed definition to it may prove fruitful.

On the one hand, in response to the advent of photography and film, modern art has drastically expanded the artistic realm by creating entire categories that never before existed:

[T]here is a fundamental value of modern art, and one that goes far deeper than a mere quest of the pleasure of the eye. Its annexation of the visible world was but a preliminary move, and it stands for that immemorial impulse of creative art: the desire to build up a world apart and self-contained, existing in its own right: a desire which, for the first time in the history of art, has become the be-all and the end-all of the artist. (66)

In other words, “Art doesn’t reproduce what we see. It makes us see.” (67) This is a worthy ambition, but oftentimes modern art, and modern artists, fail to achieve the creation of something essentially unique and meaningful, their best efforts resulting in little more than decoration, unusual curiosities or shocking statements. And shock value is short lived. Paul Johnson writes that “the central and abiding weakness of fashion art” is that “few wanted to look at their pictures twice.” (68) He sees modern art as an attack on order itself, an order necessary to maintain the civilization we know:

[I]t must never be forgotten that art was instinctively created by humanity to assist the process of ordering, and so understanding and mastering, the wild world of nature. Art is fundamentally about order…We must always look for the underlying order which runs beneath the surface of the battle, to see that it is healthy and intact, and strong enough to sustain the dynamics of change. For once art loses its fundamental order, it becomes disorderly and therefore ceases to sustain a moral society and may, in fact, become a menace to our happiness. (69)

Paul Johnson’s concern may be misplaced, as any work that successfully attacked order, structure or meaning, would itself have to contain some element of all three. If it didn’t, it would be meaningless, rendering it useless as art, and ineffective as an element of change. If he means by ‘disorderly’ an art object that attacks a specific order, be it political or social (Animal Farm for instance), criticizes a traditional structure, say within poetry (Leaves of Grass), or undermines something meaningful to a particular group (Tropic of Cancer for example), than that art object accomplishes exactly what the highest art aims to do: it forges new ground and generates aesthetic space that previously didn’t exist. If a given work makes some people uncomfortable, angry even, then it has achieved something of genuine interest, independent of our individual critical judgment:

Through the centuries, through every innovation and upheaval in art, from the poetry of the early English Romantics to the “Beat” poetry of the American 1950s, from the explosion of late-nineteenth-century European Modernist art to the Abstract Expressionism of mid-twentieth-century America, professional criticism has exerted a primarily conservative force, the gloomy wisdom of inertia, interpreting the new and startling in terms of the old and familiar, denouncing as “not art” what upsets cultural, moral, political expectations. (70)

If Oates is correct (and it rings true), then a proper definition of art should rise above such conservative bias. Critics are certainly entitled, obligated even, to rank order art objects, to judge the good from the bad, the successful from the failures. Yet to exile a work from the realm of art requires a defined standard; critical opinion alone is not enough.

This proves challenging with Modern Art, because “The ugly and discordant and senseless [have] become ‘beautiful’” according to Susan Sontag. “The history of art is a sequence of successful transgressions.” (71) These historical transgressions can be difficult for us to aesthetically assimilate:

The characteristic aim of modern art, to be unacceptable to its audience, inversely states the unacceptability to the artist of the very presence of an audience—audience in the modern sense, an assembly of voyeuristic spectators….A good deal of contemporary art seems moved by the desire to eliminate the audience from art, an enterprise that often presents itself as an attempt to eliminate “art” altogether. (In favor of “life”?)

Committed to the idea that the power of art is located in its power to negate, the ultimate weapon in the artist’s inconsistent war with his audience is to verge closer and closer to silence. (72)

This may be what Wittgenstein had in mind when he challenged his fellow philosophers to address only that which could be truly understood (very little in his view). Everything else was simply ‘language games.’ Or take the case of the ancient Chinese sage who suggested that the wiser a person becomes, the less he speaks. When asked why this was so, the sage responded (just prior to lapsing into total and profound silence): “Because it is impossible to express anything truly worth expressing.” (73) This may be true, but we artists in the West believe the opposite is also true.

“First touch me,” Diderot insists. “Astonish me, tear me to pieces, make me shudder, weep, and tremble, make me angry; then soothe my eyes, if you can.” (74) Occasionally modern art will astonish, sometimes even sooth one’s eyes. Yet rarely will it make one “shudder, weep and tremble,” let alone achieve all these things at once.

Picasso's Les Demoiselles D'Avignon

“Contemporary painters, declared Dali, painted nothing: they were non-figurative, non-objective, non-expressive in approach, and painted nothing whatsoever.” (75) Dali is right about many modern artists, and Jackson Pollack serves as a good example. Pollack had this to say about his work:

Modern art…is nothing more than the expression of contemporary aims of the age that we’re living in. (76)

The strangeness will wear off and…we will discover the deeper meanings in modern art. (77)

I think [laymen] should not look for, but look passively—and try to receive what the painting has to offer and not bring a subject matter or preconceived idea of what they are to be looking for. (78)

The modern artist…is working and expressing an inner world—in other words—expressing the energy, the motion, the other inner forces….(79)

[T]he modern artist is working with space and time, and expressing his feelings rather than illustrating. (80)

Pollack either didn’t know what he was doing and why, or was unable to articulate his approach in any way other than splashing and pouring paint on very large canvasses.

When asked by an interviewer if he had any preconceived image in mind prior to beginning a work, he responded, “Well, not exactly—no—because it hasn’t been created, you see.” (81)

None of this is very convincing or impressive, in keeping with the nature of his work (see image to the right).

Given that this work is neither meaningful nor essentially unique, it doesn’t qualify as a work of art at all.

A Jackson Pollack painting

Take another modern artist, Piet Mondrian. He begins his career as a mediocre artist painting apple trees (see example to the right) ...

Mondrian Tree

...and evolves to painting nothing more than primary colored lines, squares and rectangles (see example to the right). While arguably meaningful in some way, his works consist of simple, easily repeatable patterns that have likely been created countless times in grade schools across the country, making them common and lacking essential uniqueness.

Classic Mondrian

Or take the ever enigmatic Marcel Duchamp, who paints the wonderful Nude Descending a Staircase...

Duchamp's Nude Descending a Staircase

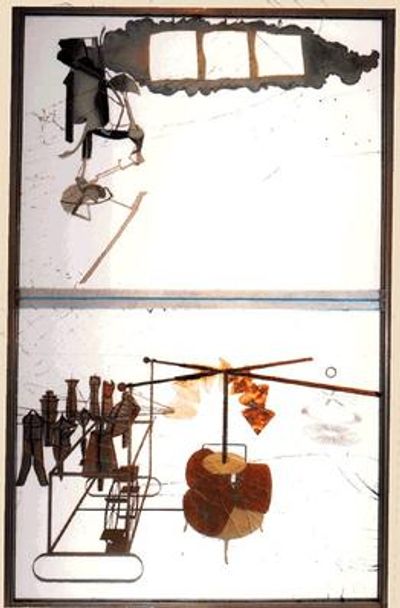

...and constructs the fascinating and enigmatic Bride Stripped Bare (images to the right)...

Duchamp's Bride Stripped Bare

...and then reverts to non-artistic stunts by placing a urinal in an exhibition as a ‘readymade’ and declares it art. Put forth unsigned by Duchamp, without serious intent, attempting to assert the (incorrect) point that anything can be made to be art (image on the right).

But this is not art, if for no other reason than it is not unique. In fact, after the original showing, the original ‘fountain’ was lost, and subsequently replaced by one identical to it. No one could possibly tell the difference, because it didn’t make any:

What interested me was why, given the attitude with which Duchamp claimed he’d made the work—in his words, ‘complete aesthetic indifference’—it was necessary to cart precisely this urinal and no other round the globe. It struck me as a complete confusion of understanding: Duchamp had explicitly been saying, ‘I can call any old urinal—or anything else for that matter—a piece of art’, and yet curators acted as though only this particular urinal was A Work Of Art. If that wasn’t the case, then why not exhibit any urinal—obtained at much lower cost from the plumber’s on the corner? (82)

All of Duchamp’s readymades fall into the same non-artistic bin: they are objects, nothing more, and placing them on a pedestal within a museum doesn’t change the fundamental nature of a wheel, a shovel, a broom. Objects yes; art objects, no.

Dada provides another excellent example. According to George Grosz, a key member of the Berlin chapter of Dada,

[Dada] was the art…of the dustbin…All the useless things people had thrown away were piled up on old planks, stuck on to canvas or tied on with wire or string, and then exhibited as so-called ‘Merz collages’ and even sold. Many critics, who wanted to be ‘in’ at all costs, praised this send-up of the public and were completely taken in by it. Only ordinary people, who knew nothing about art, reacted normally, calling Dada art garbage, rubbish and muck—which was exactly what it was. (83)

“Art that is simply a thing is an oxymoron,” Adorno writes. “Yet the development of this oxymoron is nevertheless the inner direction of contemporary art.” (84) Wittgenstein puts the case well:

But only an artist can so represent an individual thing as to make it appear to us like a work of art…A work of art forces us—as one might say—to see it in the right perspective but, in the absence of art, the object is just a fragment of nature like any other; we may exalt it through our enthusiasms but that does not give anyone else the right to confront us with it. (85)

While I find Andy Warhol’s work simplistic and uninteresting, it meets the criteria of art as it appears to be both meaningful and unique. His disrespectful attitude towards art (I don’t know if he means to be taken seriously or not), however, seems to reflect accurately on himself and the work of his fellow modern artists, when he writes that “as an artist, I make a lot of junk.” (86)

Given his ‘junky’ art, and his general lack of respect, we can understand his perspective when he writes that “Wasted space is any space that has art in it.” (87) He then reveals the key to his nature: “I never wanted to be a painter,” he admits. “I wanted to be a tap dancer.” (88) He should have followed his dream.

Consider the art critic Brian Sewell’s response to a bevy of angry modern artists:

I am not hostile to contemporary art, whatever is meant by that portmanteau term, but find much of it tediously imitative, empty of any intellectual force, sans meaning (from conceptual artists I have far too often heard the response ‘It means whatever you want it to mean,’ when a concept should surely mean only what the artist wants it to mean), certainly sans beauty, and often made in a fugitive form from fugitive materials. Why should a critic offer readers ‘an informed critique’—which in this context means no more than favorable propaganda—of so-called artists who have no skills and scant education, and whose work is far the inferior in wit, whimsy and achievement [to that] of most professional window dressers, and as short-lived? (89)

Duchamp 'Readymade'

You will find in Vermeer’s Girl Reading a Letter a stark contrast to the works Sewell regards in the response above. This is a beautiful work of art, worthy of endless contemplation and consideration, and requires no apologies or explanations:

Vermeer does not introduce us into Dutch world but into a world of tenderness and gentleness. (91)

Vermeer does represent, however, a tradition that modern art strains to go beyond, and rightfully so. Sometimes it succeeds, but at significant risk:

With the elimination of the principle of representation in painting and sculpture, and of the exploitation of fragments in music, it became almost unavoidable that the elements set free—colors, sounds, absolute configurations of words—came to appear as if they already inherently expressed something. This is, however, illusory, for the elements become eloquent only through the context in which they occur. The superstitious belief in the elementary and unmediated, to which expressionism paid homage and which worked its way down into arts and crafts as well as into philosophy, corresponds to capriciousness and accidentalness in the relation of material and expression in construction.

…Reduced to “natural material” all of this is empty… (92)

Adorno goes on to write: “The claim that there is no difference between articulation and the articulated, between immanent form and content, is seductive especially as an apology for modern art, but it is scarcely tenable.” (93) Seemingly sympathetic with Johnson’s notion of ‘Fashion Art’, Adorno hits the modern nail on the head when he wrote that “Non-representational art is suitable for decorating the walls of the newly prosperous.” (94)

Perhaps George Steiner is correct when he writes that “it is the cash nexus that has fatally split the world of art into the esoteric, at one end, and kitsch, at the other.” (95) Or Dali when he wrote “I was destined…for nothing less than to rescue painting from the void of modern art.” (96) In any case, modern art in the early 21st century may best be characterized in the following way:

Artists of our age are always offering instead of giving. They always aim at attracting rather than satisfying. Everything is suggested, with no solid foundation and no proper execution. One only needs to spend a short while quietly in a gallery, observing what works of art appeal to the multitude, which of them are praised and which are ignored, to lose all joy in the present age and have little hope for the future. (97)

On the other hand, given that this was written by Goethe over two-hundred years ago, perhaps this simply demonstrates that nothing ever really changes, and that all critiques of society and art originate from the same source: an overdeveloped sense of the intellectual self (current case certainly not excepted):

A wild imagination is intimately related to the aberrations of an over-refined intellect. (98)

Art is the ever broken promise of happiness.

Adorno, Aesthetic Theory

Vermeer's Girl Reading a Letter

Notes

- Adorno, Aesthetic Theory

- Mikel Dufrenne, The Phenomenology of Aesthetic Experience

- anonymous dissertation, http://igitur-archive.library.uu.nl/dissertations/1938487/c3.pdf

- Weitz, The Role of Theory in Aesthetics

- George Dickie, The Institutional Conception of Art

- anonymous dissertation, http://igitur-archive.library.uu.nl/dissertations/1938487/c3.pdf

- ibid

- Mikel Dufrenne, The Phenomenology of Aesthetic Experience

- Adorno, Aesthetic Theory

- Terry Eagleton, Illusions of Postmodernism

- David Daiches, The Novel and the Modern World

- James L. Weaver, web

- Ibid

- Ayn Rand, The Romantic Manifesto

- Ronald Merrill, The Ideas of Ayn Rand

- Ayn Rand, The Romantic Manifesto

- Adorno, Aesthetic Theory

- Malraux, Voices of Silence

- Joseph Schumpter, quoted by Thomas McCraw in Prophet of Innovation

- Adorno, Aesthetic Theory

- Walter Benjamin, Selected Writings, Vol. 1

- Gore Vidal, United States

- Adorno, Aesthetic Theory

- Ayn Rand, The Romantic Manifesto

- Shah Jahan, web

- Schiller, Essays

- Gadamer, Truth and Method

- Robert Musil, The Precision and Soul

- Susan Sontag, Styles of a Radical Will

- Shannon Wheeler, Personal Communication

- Paul Johnson, Art: A New History

- Jeannette Winterson, Art and Lies

- E. M. Cioran, Anathemas and Admirations

- Mikel Dufrenne, The Phenomenology of Aesthetic Experience

- Joyce Carol Oates, The Aesthetics of Fear

- Adorno, Aesthetic Theory

- Auden, The Dyer’s Hand

- quoted from the web - unable to attribute

- Ibid

- Adorno, Aesthetic Theory

- Ibid

- Taschen, Dali – Volume II

- Sartre, What is Literature

- Nietzsche, The Will to Power

- Alfred Kazin, Contemporaries

- Edward Casey, quoted by Mikel Dufrenne in The Phenomenology of Aesthetic Experience

- F. R. Leavis, The Critic as Anti-Philosopher

- Terry Eagleton, Literary Theory

- Peter Watson, Modern Minds

- John Aldridge, After the Lost Generation

- Art Berman, From the New Criticism to Deconstruction

- Mikel Dufrenne’s The Phenomenology of Aesthetic Experience

- George Steiner, My Unwritten Books

- Adorno, Aesthetic Theory

- Ibid

- John Gardner, Writers and Writing

- Adorno, Aesthetic Theory

- Harold Bloom, The Visionary Company

- Gautier, quoted by Roger Shattuck in Candor and Perversion

- Nietzsche, Untimely Meditations

- Adorno, Aesthetic Theory

- Mikel Dufrenne, The Phenomenology of Aesthetic Experience

- Goethe, Wilhem Meister’s Apprenticeship

- George Steiner, Real Presences

- Annie Dillard, Living by Fiction

- Andre Malraux, Voices of Silence

- Picasso, quoted by Joyce Carol Oates , Where I’ve been and Where I am Going

- Paul Johnson, Art: a New History

- Ibid

- Joyce Carol Oates, Art and “Victim Art”

- Susan Sontag, Styles of a Radical Will

- Ibid

- Anonymous sage

- Diderot, Grove Book of Art Writing

- Taschen, Dali – Volume II

- Jackson Pollack, Grove Book of Art Writing

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Brian Eno, The Grove Book of Art Writing

- George Grosz, The Grove Book of Art Writing

- Adorno, Aesthetic Theory

- Wittgenstein, Culture and Value

- Andy Warhol, Grove Book of Art Writing

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Brian Sewell, Grove Book of Art Writing

- Mikel Dufrenne, The Phenomenology of Aesthetic Experience

- Adorno, Aesthetic Theory

- Ibid

- Ibid

- George Steiner, A Reader

- Dali, The Secret Life of Salvador Dali

- Goethe, Wilhelm Meister

- Treitschke, quoted by Walter Benjamin